[Non-fiction]

We’ve just left Garden Island. My wife Erica, Marlowe and I are standing on the foredeck of the Supercat Susie O’Neill, a modern Sydney Harbour ferry, working the route east from Circular Quay to Watson’s Bay. The deck thrums evenly, erasing the waves with the sheer power and bulk of the boat. My one-and-a-half year old son is crooked into my right arm, squinting into the sun and wind, blond hair plastered to one side of his face, which is scrunched into a disapproving contortion of his usually angelic disposition as he looks out over the massive steel gunwales of the ferry. He is trying to unlock the mysteries of the host of sparkles that seem to run parallel to us across the water. The wind works his red baseball cap free and slaps it to the deck a few metres away. Erica deftly snatches it up and jams it tighter on his head. She tries, in vain, to secure it against the brisk force of the wind, but it’s all around us, pressing against us, forcing us to lean into it.

I look out across Sydney Harbour and start to do what I came here for. I try to photoshop the scene of the disaster into this idyllic setting. To gain some comprehension of what it must have been like for the everyday to be shattered by such terror. No matter how hard I try, it’s all stick figures and toy boats. Why did I come? It’s just a normal ferry, a normal Sunday morning.

The ferry reaches a point almost directly across from Bradley’s Head. Way down below us the never-salvaged rusted detritus of the exploded boiler of the Greycliffe must lie. Here is where it must have happened. Surely something will happen to me now, a wave of dread, a momentary wash of sweat across my brow, an unexpected lurch from beneath the bowels of the ship in some sort of a timeless echo of the disaster. Nothing happens. We glide seamlessly through the sunlight, surrounded by commuters and tourists, on the blunt prow of the Supercat. Only in my imagination can I see all the marks of history erased by more history, all the works of men undone by younger men, the shifts of power across time, counter-struck by fresher minds.

I try to piece it together.

In 1927, at age 22, the fourth-year medical student Alexander Inglis ditches a class at Sydney University, in which he “had not shone brightly”[i], rushes to Circular Quay, only to see the early ferry departing. Lobbing his bag over the side, he just manages to leap aboard in time before the last gap in the gunwales passes the end point of the pier. It is the Greycliffe.

Alexander considers himself lucky to have so narrowly escaped the tedium of being shore-bound and retrieves his bag. He takes himself upstairs to his customary position in the men’s upper deck saloon of the ferry’s forward section . Lucky again, he finds his favourite seat vacant. Luckier still, a gentleman doctor who he knows by sight is conversing with two other doctors not far away. He had often eavesdropped on their conversations as the ferry made its hour-long journey across the harbour to Watson’s Bay. He has a naturally inquisitive mind, and hearing these men talk about their jobs is perhaps a window into what his own future might hold.

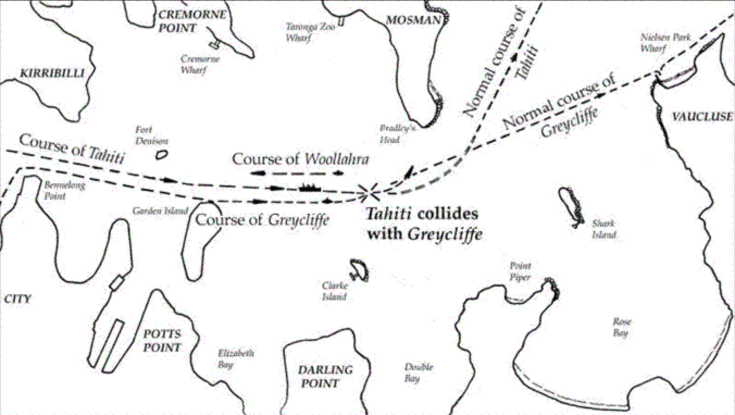

From behind the Greycliffe, his immediate future is rapidly approaching, at the rate of 17 knots, and with inadequate sea-room, in the form of the S.S. Tahiti, a 460ft passenger liner en-route to America.

The ferry docks and departs from Garden Island, and has just reached this position – just opposite Bradley’s Head – when Alexander, for some unknown reason, turns his head sufficiently to see the bow wave, and the vast iron expanse of the hull behind it, fast approaching. Alex gauges a collision is imminent, but hesitates; no one else on the comparatively small ferry sees anything amiss. He feels like a spell needs to be broken and it is up to him to do it. Everything is completely normal, but the impossible is about to happen, and indeed, is happening. He shouts, “Look out!” [ii] and leaps out the door into the open air. He scrambles past the gunwales for the second time that day, and dives into the chilly November water. The shock of the water sobers and intimidates him. He fears he might have made an idiot of himself. Treading water, he witnesses the bow of the Tahiti strike the Greycliffe amidships. The implacable momentum of the 7600 ton ship pushes the Greycliffe’s bow perpendicular and she rolls into the water.[iii] It is with an odd mixture of relief (that he hadn’t made a fool of himself) and horror that Alex watches the little ferry as it’s pushed – as he had feared it would be – beneath the bows of the leviathan.

The Greycliffe is cut in two. Some jump to safety, but far too few. He doesn’t hear the boiler of the steamer implode as it is swamped with cold water.[iv]

The massive bubbles of trapped air that rise to the surface are replaced by a rush of water in the opposite direction, inexorably downward, taking Alex with it. He sees the sides of the great passenger liner pass by him; a dark “chocolate brown”[v] smear across his vision. Nearer, wreckage tumbling through the confused mass of bodies and steel and wood and bubbles of air seeking release far above his head. He follows them upward and breaks the surface, still dangerously close to the massive bulk of barnacles and rust-flaked iron, tumbled about by flotsam as it is pushed aside in the white water of the ship. His next thought is of the propellers, but as he comes nearer to them he sees that they are turning only very slowly.

He passes the propellers safely and finds a piece of wooden wreckage about 10’ by 10’[vi] and hauls himself up onto it. He hears a call.

“Pull on me, I can’t swim.”[vii]

A man is only just keeping his head above water. It is Barratt, a man he knows by sight, an engineer aboard the Greycliffe. The water around them is stained with blood, and Alex thinks only of the possibility of shark attack. He drags Barratt up onto the raft. Alex finds that Barratt has a fracture just below the knee and that there is copious blood squirting from it. Barratt’s face is white as he stares into the sky, framing Alex’s darkened face as he wonders what to do.

Alex looks around. There is no doubt that Barratt is going to die unless he does something, but it seems his mind has been wiped clean. For a moment he just shivers, staring into the wind coming off the whitecaps and chilling the harbor water that soaks him to the skin. How many people were dying below him in the deep green water? Aside from the waves lapping at the sides of the raft, in the wake of the Tahiti the harbour seems oddly still.

The blood from Barratt’s leg is dripping from the side of the raft into the water. Sharks. The fear gives him focus. Attached to the flotsam that bears the two men is a life vest. Attached to the life-vest is a thin canvas belt that runs along the lower edge used to secure it to the waist. The belt reminds him of a class he had taken only that very morning, when he had been instructed how to most effectively tie a tourniquet. The information is still fresh in his mind. (He doesn’t know it yet, but it is the only tourniquet he will ever apply in his long career as a doctor.)

The flow of blood is stopped.

Barratt will lose the leg, but there is no doubt that Alex saved his life. (Later, no longer able to pursue his career as a ship’s engineer, Sydney Transport will give Barratt a post selling tickets, and from that day on, if Barratt was in the booth, Alex would always be waved away with the words: “On you go, doctor.”[viii])

The wait upon the little raft seems endless, and the wind has nearly blown their clothes dry by the time a police boat arrives. It transports them to the Man O’War steps, by the Opera House. From there they are taken to Sydney Hospital.

All available doctors in the area are called to care for the maimed survivors. To his horror, he sees that it is his very own lecturer from Sydney University that he’d dodged hours before. The man’s eyes widen, clearly recognising him, but only says, “And what’s the matter with you?”

“Nothing sir,” says Alex.

The registrar regards him for a second or two, turns to the nurse, and says, “Immersion, admit him.”[ix]

Within a week, complete notes for the entire year find their way into Alex’s hands, care of his lecturer. No word is said. Alexander Inglis finishes his medical degree two years later, but he can never think of that day without sadness for the three doctors in the saloon who had been taken down with her. They were the ones engrossed in conversation, while he, the idler and truant, had the time in those few critical moments to see what was about to happen, and to act.

He would speak of the ordeal for many years afterward. “It was his way of coping with it,” I remember his daughter, Georgie, saying to me. “There was no such thing as post-traumatic stress syndrome in those days.” [x]

Years later, Alex meets Georgie’s mum aboard the Orsova, a trans-Atlantic cruise ship. Tired of the usual boring fare the captain’s table has to offer, he asks the ship’s captain to seat him next to “a looker”[xi]. He finds himself next to Phyllis Bayley, and they hit it off straight away. The pair married only two weeks later, beating his potentially disapproving family to the punch.

Out on the windy foredeck of the ferry, Marlowe is starting to get heavy but I don’t want to put him down yet. The events of someone else’s past blink and ring like pinballs bouncing around inside my skull. We are leaving the area now, coming into Double Bay wharf. The old ferry route didn’t include Double Bay. I begin to wonder if we’d ever been near the actual place of the collision at all. Did it matter? The events are long gone, they existed in my mind. Why the need to be at the precise spot anyway?

Maybe the answer is the same for the people revisiting Ground Zero, or Auschwitz, or the killing fields of Cambodia. I don’t think it is merely a grotesque fascination. There is something that runs deeper, that goes into almost every edifice we place around us from city to country. It is an attempt to beat death, to place it, to rationalise it, to understand it. To institutionalise it.

It never works. The memorial to the Greycliffe rests at Lady Macquarie’s Chair–like the Titanic memorial in Washington D.C.–on solid ground.

I am just beginning to put down our time aboard the Susie O’Neill as a dead end, anecdotal at best, when two weeks later something happens which brings a fresh perspective on things.

Having just arrived home from work, I sweep Marlowe up and carry him down the hall to the bedroom for a big hello bounce on the bed: a nightly ritual. He knows what’s coming and giggles in anticipation of the ride as he clings to me. Standing over our queen bed, in an attempt to slow things down a bit, I give him a count of “One, two, three!”

I let go.

His expression of pure joy turns to a grimace of pain. He bounces a second time, and brings his arm out, crying, “Arm? ARM! ARM!”.

It’s bent unnaturally, right between his little forearm and wrist.

At the hospital we find that his arm is broken in two places. They put the cast on. His hoarse, choking screams wear themselves out to thin rasps. He gulps for air, and it begins again.

When we finally get home, I immediately search the bed under the doona, through a haze of guilty tears, for a hard object, a scapegoat, anything to explain it. There is nothing. Drop a little boy on a soft bed from three feet up – he breaks his arm. No matter how often the scene plays itself out for another forensic examination, there is no cause. How can I learn from it? I can’t. What action can I take to protect him next time? None. I would have happily offered my own arm up to break in his place. Then, in the overturned bed, it hits me: could this have been how Alex felt, surviving so much pain unscathed?

I think of Phyllis and Alex’s flash wedding. Their daughter, Georgie Inglis married David Baron, and had three daughters. Unexpectedly, in 1980, they had a fourth: Erica Baron, Alex’s granddaughter, brought up with just enough questionable judgement to become my wife.

I think of her deep green eyes regarding me soulfully as she stands on the deck, buffeted by wind, on that bright and sunny Sunday. She’s still there, in my mind. We both knew then she was pregnant with our second child, and it informed the minutiae of her glances and movements. The knowledge of that coming event pervades and steers us.

What about the things we cannot see?

I think Alex knew. As time passes, the wind blows harder, and we lean in. We become part of it and it of us. The present never stops becoming the past, and fluid as the fecund sea, we join with the lost.

Dedicated to the 40 souls lost aboard the Greycliffe.

Rest in peace.

(First published in LINQ Journal, 2013 edition)

Leave a comment