[Review]

Imagine falling asleep right there in the cinema, at a film festival with films screening back to back. Suddenly, a strange man who doesn’t belong in these movies breaks the fourth wall and begins addressing you about how the films are affecting you, deconstructing each film before your eyes.

Like an intellectual gremlin, the strange man walks from They Live to The Searchers to Taxi Driver to The Sound of Music to A Clockwork Orange, explaining each film in a startling light. He looks like a cross between Con the Fruiterer and Sigmund Freud, complete with a lisp and thick Slavic accent.

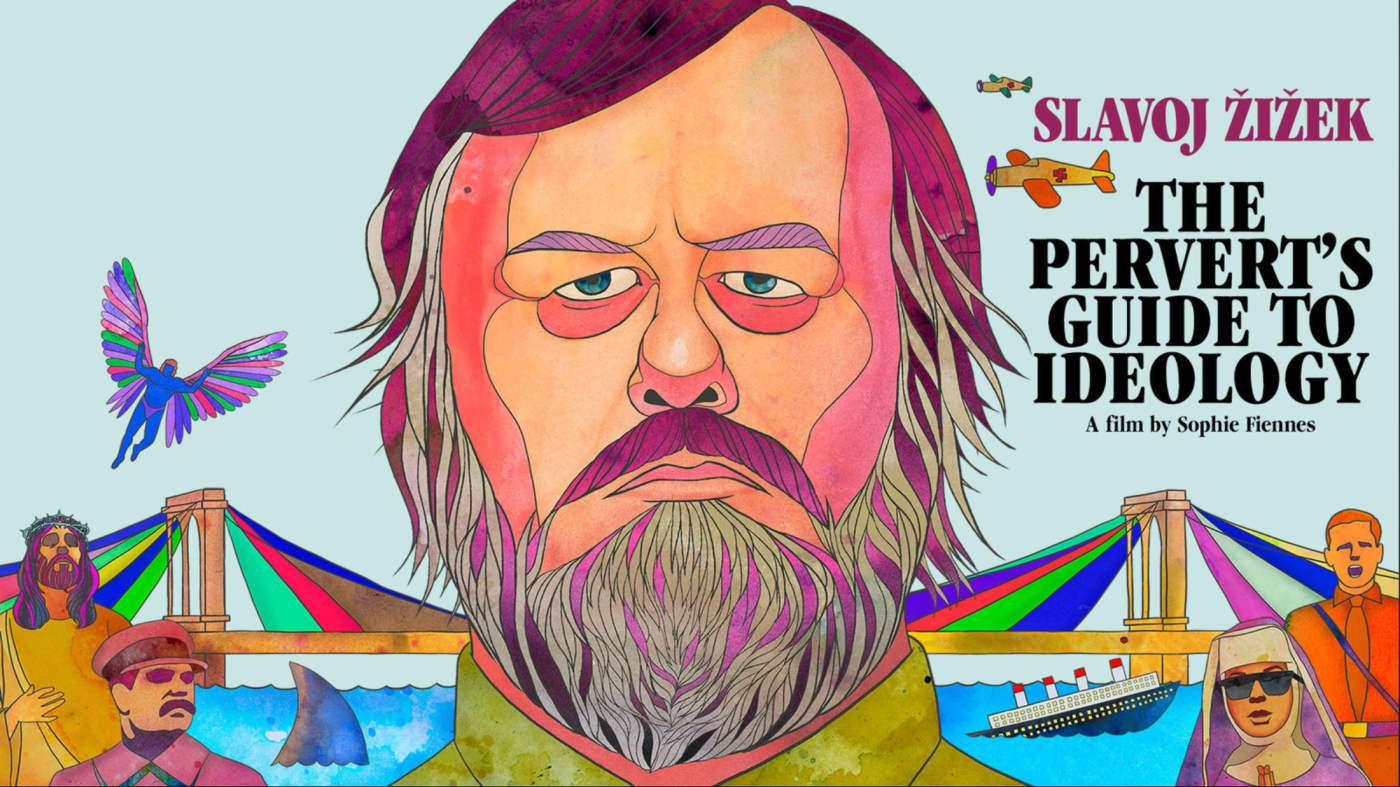

This is none other than Slavoj Žižek, a Slovene philosopher and cultural critic. He is a senior researcher at the Institute for Sociology and Philosophy, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia, and a professor of philosophy and psychoanalysis at the European Graduate School. Directed by Sophie Fiennes (sister to Ralph and Martha) the film consists of a clever directorial trick of a free flowing speech delivered by Žižek across the sets and locales of the aforementioned films, imposing himself on the narrative and context in order to challenge it and adroitly address where it comes from, and more importantly, where it is going.

The film also references current acts of terrorism and senseless violence, but not with the usual single-minded copycat theories that we more commonly see in the press. The idea is to reverse-engineer violence in film in order to easier understand its seeming senselessness. It is very effective.

The Perverts Guide to Ideology isn’t for everyone. It’s a didactic film that flies in the face of the old adage of “show, don’t tell”. But that’s all right. It’s a documentary, right? I instinctively have reservations about anyone telling me how to interpret a work of art, and at this point you might say ok and stop reading, but just for arguments sake I will continue and hope you haven’t. In spite of being instructed demonstratively about context, I found the content illuminating and I have to admit has enabled me to see conflict in film in an entirely new light.

Žižek’s impassioned, idiosyncratic delivery is in thickly accented English, and can be at times difficult to make out. I found myself subjectively grinning at the audacity of the film and Žižek’s accent. Occasionally he gives the impression of starting sentences he’s not sure how to finish. They can be long, convoluted and over-emphasized so much that meaning is sacrificed – a shame because what he was saying seemed important. I found my hand reaching for the rewind button on more than one occasion. In spite of all that, I thoroughly enjoyed myself and would recommend the film to anyone looking for a new way to interpret cinema and current events.

If you were a fan of Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, but have been craving something a little more erudite, you’ll love this one.

(First published in Megaphone Oz, 2013)

Leave a comment